Confinement

15 October – 18 December 2020

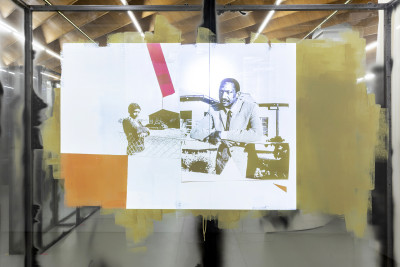

ETH Zurich, Hönggerberg

Confinement is a collaborative exhibition taking place both online at e-flux Architecture and on site at ETH Zürich, curated by gta exhibitions (Fredi Fischli, Simona Mele, Niels Olsen, Irma Radoncic, Meghan Rolvien, Sara Sherif, and Jeremy Waterfield) and e-flux Architecture (Nick Axel and Nikolaus Hirsch), featuring contributions by 2A+P/A, David Adjaye, Chino Amobi, Aristide Antonas, Armature Globale, Alessandro Bava and Lydia Ourahmane, Inside Outside / Petra Blaisse, Andrea Branzi, Rebecca Choi and Roland Bedford, Design Earth, Dogma, Pezo von Ellrichshausen, Joana de la Fontaine, Manuel Gnam, Itsuko Hasegawa, Trix & Robert Haussmann, Samia Henni, Andres L. Hernandez, Momoyo Kaijima, Michel Kessler, Semuel Lala, Léopold Lambert and Roanne Moodley, William Leavitt, MAIO, Catherine Malabou, MILLIØNS, Freek Persyn, Pedro Pitarch, Space Popular, sub and Celeste Burlina, Emmanuel Pratt, Smiljan Radic, Jack Self, Traumnovelle, Sumayya Vally, Jan de Vylder and Inge Vinck, Jakob Walter, Eyal Weizman, SITE - James Wines, Ilze Wolff, Lydia Xynogala, Alberto Lule, Savannah Ramirez, Rosie Rios, Nathaniel Whitfield and more.

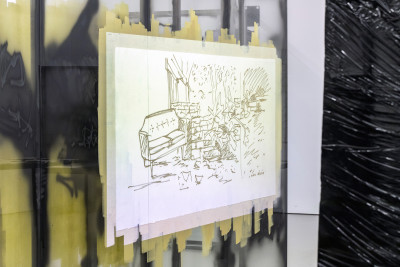

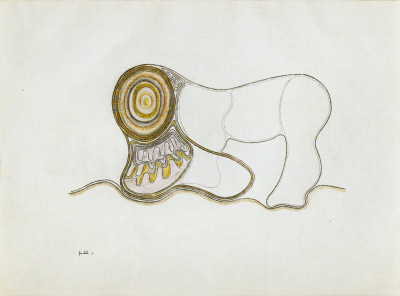

The exhibition is the outcome of an open, collective discussion that started at the beginning of 2020 about how to understand the current conditions of life and what implications they might have for the discipline of architecture. We observed how classical techniques of confinement have dramatically expanded, their domains of oppression building upon historical forms of institutional violence. From the virus to the room, the screen, and the municipality, todays social separations create new modes of behavior. We reflected on the archaic media format of the drawing and its potential to trace and express the current environment and its rapidly changing conditions. Paradoxically, the drawing has been resurrected with growing attachments to screens. The flatness of paper adapts itself to any given digital device, but not without efforts and opportunities of translation. The contributions collaboratively shape a script-like and additive exhibition. To kick off this discursive forum, we invited Samia Henni, Assistant Professor at Cornell University’s Department of Architecture, College of Architecture, Art and Planning, and researcher on architectural violence, to reflect on the project’s title:

Captivity, containment, custody, detainment, detention, enclosure, entrapment, house arrest, immurement, impoundment, imprisonment, incarceration, internment, isolation, quarantine, restraint, or segregation, are all possible synonyms for the term “confinement,” which entails both the act of confining and the state of being confined. However, being in solitary confinement, or in prison, whether for life or not, is not the same as being in a temporary quarantine, wherever that might be. The term confinement was also used to refer to the condition of women of being in childbirth at home or at the hospital. Etymologically, the term derives from sixteenth-century Old French word confinacion, which stems from the term confiner, that is “to border, to shut up, to enclose,” which most probably originates from the Medieval Latin term confinare, which means “to border on, to set bounds, to keep within limits.”

A few months ago, the French government and media added another signified to the term. On March 16, 2020, the French President, Emmanuel Macron, addressed the nation and announced new measures to slow down the spread of Covid-19 in France. Macron declared that, “From noon tomorrow and for at least fifteen days, our trips will be greatly reduced.” These restrictions had to be respected “everywhere in France, in metropolitan France and oversea,” and “any violation of these rules will be penalized.” Popularized by the expression “confinement of the population,” this mandatory and sanctionable travel ban lasted until May 11, 2020, and was employed further by other countries, including France’s former colonies, and translated into other languages.

Titling an exhibition Confinement in 2020 suggests not only the act of confining individuals or masses, but also the very state and status of being confined in one’s cell, room, refuge, self-built shelter, asylum, camp, apartment, house, villa, or palace. The experience that one might have with the fact of being confined depends not only on the cause and space of confinement, but also on questions of ability, age, class, gender, sexuality, race, and other intrinsic issues related to the state and status of the confined. Moreover, imposing confinement on the entire population of a nation only further endangered unhoused people as they lost their basic right to live in the streets of that very confined nation.

While portraying confinement is not, and cannot be, detached from the nature of the experience—if any—of confinement, the portrayal of confinement might not, and cannot, coincide with the experience—if any—of being confined. It is, indeed, “to keep within limits.”

This project is supported by the Adrian Weiss Stiftung and the ETH Zürich Foundation.

Photos: Nelly Rodriguez