Beverly Buchanan

I Broke the House

6 March – 17 May 2024

Opening: 5 March 2024, 6 pm

With contributions by Elena Bally, Jennifer Burris, María Magdalena Campos-Pons, Aria Dean, Fredi Fischli, Jack Halberstam, Harvard University GSD students, Alicia Henry, Anna Gritz, Tonja Khabir, Parity Group, Prudence Lopp, Park McArthur, Devin T. Mays, Ana Mendieta, Siddhartha Mitter, Kazuko Miyamoto, Senga Nengudi, Niels Olsen, Sarah Richter, Cameron Rowland, Jamaal Sheats and Adam Szymczyk

Roundtable: 5 March, 4 – 5.30 pm, HIB E 52 (Open Space 2), ETH Zurich, Hönggerberg

In collaboration with Parity Group, Parity Talks IX: “On Inconvenience”

With María Magdalena Campos-Pons, Anna Gritz, Tonja Khabir, Prudence Lopp, Devin T. Mays, Siddhartha Mitter, Sarah Richter, Jamaal Sheats and Adam Szymczyk

Closing event: 14 May 2024, 6 pm, gta exhibitions, ETH Zurich, Hönggerberg

Talk with Jack Halberstam

Curated by gta exhibitions, ETH Zurich in collaboration with Tubman African American Museum, Macon, GA; Fisk University Galleries, Nashville, TN; Engine for Art, Democracy and Justice (EADJ), Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN

This exhibition is indebted to the Artist-in-Residence Program made possible by the Thomas and Doris Ammann Foundation.

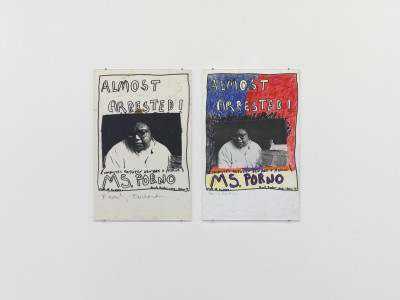

“I BROKE THE HOUSE,” screams Lila, the protagonist of Beverly Buchanan’s artist book. “Every day, Lila walked past houses sitting on rocks.” Those stacks of stones, similar to ancient cairns used as place markers, support the entire building; nevertheless, Lila suspects “they look like they could be pushed over on the ground.” One can understand the temptation to challenge the seemingly precarious structure, and so, “one day, Lila decided to take away one of the small rocks… guess what happened!”

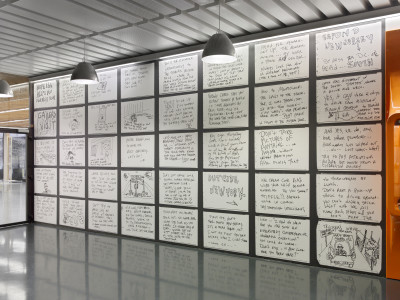

What potential lies dormant within scenes of collapse?[i] How does a house as an agent of its own resonate with, respond to or resist its surroundings? As a landscape of scattered and discarded debris, the exhibition is titled after Beverly Buchanan’s tale of Lila and the collapsed house, captured in her humorous, cartoonish fanzine. Drawing on the artist’s attention to the notion of decay, the show raises the question: what is created when something comes apart?

I Broke the House at ETH Zurich spans Buchanan’s wide-ranging oeuvre of sculpture, painting, photography, drawing, writing and printed matter. It enters into dialogue with works by Senga Nengudi, Ana Mendieta, Kazuko Miyamoto, Park McArthur and Jennifer Burris, Cameron Rowland, Devin T. Mays, Aria Dean and Alicia Henry. As a study of Buchanan’s artwork, the exhibition gathers fragmented materials by an artist who defied official mechanisms of commemoration and classification. Her practice traces eroded surfaces of ‘City Ruins’ on canvas and paper, researches vernacular dwellings and their ‘builder-occupants’ in the rural South and persistently embeds long-neglected histories of anti-Black politics in their territorial surroundings. In the context of a gallery attached to an architecture school, Buchanan’s work—predicated on critical engagement with the built environment—challenges the normative formats and politics of “exhibiting architecture.” By investigating and undoing solid structures, Buchanan confronts viewers with unsettling readings of sites, buildings and memorials in solidarity with communities that resist authoritarian narratives.

Beverly Buchanan (1940–2015, b. Fuquay, North Carolina) worked as a health educator and medical technologist in New Jersey and the Bronx while taking classes with Norman Lewis, a painter and founding member of the artist group Spiral, at the Art Students League in New York.[ii] It was there that Buchanan began to make large abstract paintings of walls. Initially using bright acrylic colors, she later reduced her palette to black. To render the dilapidated appearance of outside walls affected by time, weather and pollution—what Buchanan described as “the aesthetic qualities of decay”[iii]—she used both brushes and paint rollers, gradually shifting between lighter and darker areas on the canvas.[iv]

By the mid-70s, the Wall Paintings had evolved into sculptural works made of concrete, using found objects such as bricks or cardboard boxes as molds. Buchanan then arranged the sculptural fragments on the floor like piles of rubble. Opposing the predominant language of Minimalism, Buchanan visibly emphasized the intense physical labor involved in their creation through their rough materiality. Similar to the Wall Paintings, her sculptures—or Frustulas (Latin ‘piece’ or ‘fragment’) as she calls them—can be read as abstractions of the social and economic histories embedded in the urban environment that she encountered while living in New York—notably, a time when the property market bubble burst worldwide, leading to the city’s fiscal bankruptcy in 1975.[v]

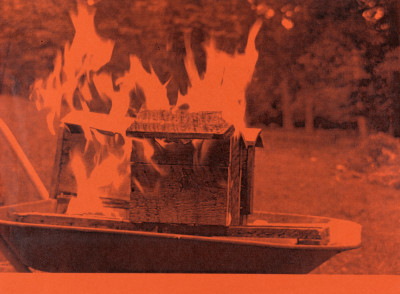

Upon leaving her job in the medical field and moving back South, to Macon, Georgia, in 1977, Buchanan began working on her environmental sculptures, intensifying her investment in labor-intensive practices and the performativity of material processes.[vi] Built to eventually dissolve into their environment, the sculptures question the politics of commemoration and place, resonating with the memory of racial violence that is under threat, said to be a thing of the past while persisting in a very real socioeconomic present. In this sense, her environmental works—Ruins and Rituals, Marsh Ruins or Unity Stones—do not invite a nostalgic or romanticized reading of sculptural ruins, but instead point to the ruination in their current surroundings.[vii] As elusive, abstract and modestly scaled public artworks with no mediating signage, they don’t add spectacle to the landscape in which they are placed. Instead, often barely visible, they act as subtle place markers.[viii] Unlike the remote sites commonly associated with Land Art, they are situated in urban districts and in close proximity to communal spaces.

South Inside Out (1990), a life-size wooden shack, its interior turned inside out, is part of the research into self-made houses of the rural South that Buchanan conducted for well over three decades. She explored the theme in a variety of media, including painting, oil pastel, crayon, cardboard, metal, wood and writing. In her artist books documenting the shacks nestled among trees “south from Athens, Georgia” or standing next to a road, separated only by a narrow strip of maize, Buchanan describes them as “survivors,” most likely alluding not just to the dwellings that fly in the face of neoliberal housing policy but also to the resilience of their builders and occupants.[ix] South Inside Out is essentially also a “survivor”: the shack was rescued, disassembled and stored at the Tubman Museum in Macon after Buchanan passed away in 2015. For I Broke the House, gta exhibitions restored the work together with the Tubman Museum, based on archival images as well as the artist’s sketches and notes.

Learning from the communal trajectory of Buchanan’s works—closely intertwined with their built, natural and socio-cultural surroundings—the exhibition brings together the voices of her contemporaries as well as contributions by contemporary artists, scholars and activists. Addressing the collective spaces Buchanan engaged with in New York during the 1970s and early 1980s, the show includes archival materials on the Cinque Gallery—a space dedicated to the work of African-American artists, founded in 1969 by Norman Lewis, Romare Bearden and Ernest Crichlow— and the A.I.R. Gallery, established by twenty artists as a women’s cooperative gallery in 1972. The dialogue between Beverly Buchanan’s works and Senga Nengudi’s Water Composition III, Ana Mendieta’s Gun Powder Silueta and Kazuko Miyamoto’s Bowery Mission Kimono constitutes a specific case study of the 1980 group exhibition Dialectics of Isolation at A.I.R. Gallery—a space where the politics of aesthetics were discussed and negotiated from the self-identified position of Third World Women artists.

The exhibition includes works by Cameron Rowland, Aria Dean, Alicia Henry, and a site-specific installation by Devin T. Mays. A three-channel video by artists Park McArthur and Jason Hirata and curator Jennifer Burris documents Buchanan’s environmental works and a library of books explores Buchanan’s practice as a critical form of “exhibiting architecture.” The books were created by Harvard University GSD students in a research seminar taught by the exhibition curators. Further contributors include the scholar Sarah Richter, the author Jack Halberstam, the curator Adam Szymczyk, and the community activist Tonja Khabir. Khabir is working on re-opening the Bobby Jones Performing Arts Center in Macon, just across the street from Buchanan’s Unity Stones in the Pleasant Hill district.

Curated by the team of gta exhibitions, Elena Bally, Fredi Fischli and Niels Olsen, the exhibition is a collective undertaking. Park McArthur and Jennifer Burris laid the groundwork for this project with their exhibition and book, Beverly Buchanan—Ruins and Rituals, at the Brooklyn Museum and the Spelman College Museum of Fine Art (2017). Their profound insight has been invaluable in the making of this exhibition. Jack Halberstam, Quinn Harrelson, Charlotte Matter, Precious Okoyomon and Siddhartha Mitter also contributed inspiring thoughts to this endeavor early on. Thanks to María Magdalena Campos-Pons, Tennesse Triennale in Nashville and Engine for Art, Democracy and Justice at Vanderbilt University, Adam Szymczyk and Niels Olsen were able to make a foundational research trip through Georgia. Szymczyk’s contribution to the curatorial process was instrumental. Prudence Lopp tirelessly supported the planning of the exhibition and made numerous loans available. We are grateful to Jeff Bruce and the team of the Tubman African American Museum in Macon for loaning us the large-scale shack sculpture, which hasn’t been shown in decades. Jamaal Sheats, curator and director of Fisk University Galleries, is committed to this long-term project and envisions a second iteration of the exhibition in Nashville. In 2025, an exhibition of Buchanan’s work will take place at Haus am Waldsee, Berlin, which is being developed in close collaboration with gta exhibitions and its partners. Susan Cary of The Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, provided numerous archival loans to the exhibition, as well as Aurélie Bernard Wortsman, the director of Andrew Edlin Gallery, New York. Uri McMillan, Sarah Richter, Dolores Hayden, Susan Stedman, curator of Creating Community. Cinque Gallery Artists, Eva Fabbris and Chiara Lupi of the Madre museum in Naples, among many others, provided important advice. The students of the Harvard University GSD who attended the research seminar led by Fredi Fischli and Niels Olsen in fall 2023 (Manuel Bouzas Barcala, Jonathan Caron, Keeley Chism, Adrian Corbey, Song Dong, Emily Eggers, Leon Fong, Fernando Garrido Carreras, Finn Rattana Hok, Noemi Iten, Yeonho Lee, Galena Sardamova, Kirsten Sexton, Sahar Simforoosh, Alyona Sotnikova, Kaleb Swanson, Tracy Tan, Olivia Tremml, Tristan Whalen, Bryan Wong and Juno Zhu) contributed to the many discussions and engaged in research that shaped this exhibition, along with numerous guests, who joined the course, among them Jane Bridges, Leigh Arnold, Jana LaBrasca and Teo Schifferli. Last but not least, the exhibition would not be possible without the tireless efforts of the team of gta exhibitions, Olin Petzold, Noé Lafranchi, Mina Hava, Daniel Sommer and Sabine Sarwa.

Cover: Beverly Buchanan, Out of Control, 1991, Scrapbook, Beverly Buchanan papers, 1912-2017, bulk 1970s-1990s. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Installation views: Annik Wetter

[i] Jack Halberstam, “Unbuild the World!,” Revolution 13/13—13 Revolutionary Philosophers/13 Seminars at Columbia, 2021–2022, February 20, 2020, https://blogs.law.columbia.edu/revolution1313/jack-halberstam-2/.

[ii] Cf. Park McArthur and Jennifer Burris Staton (eds.), Beverly Buchanan: 1978–1981 (Mexico City: Athénée Press, 2015), 12.

[iii] Beverly Buchanan Papers, Series 3: Writings, 1960-circa 2009, Box 2, Folder 27: Color Interpretations of Urban Ruins: Torn Wall Series Part Three; The Wall. The Core of Its Meaning Notebook, 1976-1980, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution Washington, D.C. 20560.

[iv] Cf. Lowery Stokes Sims, “Home is Where the Heart is: Beverly Buchanan’s Shack Sculpture in Context,” in Beverly Buchanan: Shack Works, ed. Eleanor Flomenhaft (New Jersey: The Montclair Art Museum, 1994), 33.

[v] Cf. David Harvey, “The Right to the City,” in New Left Review 53, Sept./Oct. 2008, 28.

[vi] Cf. Beverly Buchanan, Beverly Buchanan (ca. 1982), Beverly Buchanan Papers, Series 3: Writings, 1960-circa 2009, Box 2, Folder 24: Artist Statements and Writings by Beverly Buchanan, 1981–2001, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution Washington, D.C. 20560.

[vii] Cf. Andy Campbell, “‘We’re Going To See Blood on Them Next:’ Beverly Buchanan’s Georgia Ruins and Black Negativity,” in Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge, Issue 29 (2016), http://www.rhizomes.net/issue29/pdf/campbell.pdf.

[viii] See Dolores Hayden, The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1995.

[ix] Beverly Buchanan, Survivors (undated), Beverly Buchanan Papers, Series 10: Artwork, Box 14, Folder 2, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution Washington, D.C. 20560.